The Amazon Flywheel by Sam Seely

In the early 90s, while working at D.E. Shaw, Jeff Bezos incubated his initial idea for Amazon.com, a business that used the internet to offer customers a larger selection of goods at a lower price than competitors. These two facets -- greater selection and lower price -- are the foundation of Amazon’s leading principle: customer obsession.

What started as a guiding principle of offering the greatest possible selection at the lowest possible price, no matter what, evolved into a larger business model (and mechanism of growth) than Amazon ever realized it had in its early years.

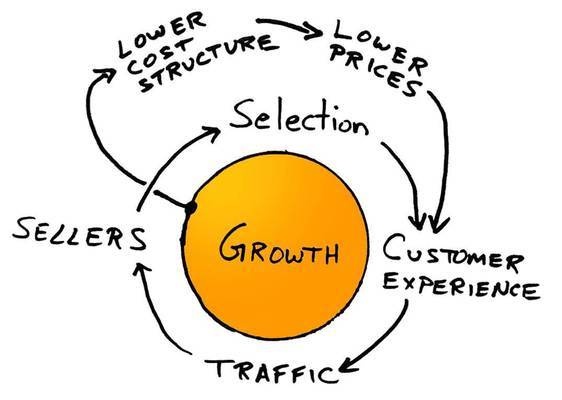

This business model is the Amazon flywheel, an economic engine that uses growth and massive scale to improve the customer experience through (again) greater selection and lower cost. Amazon first discovered its magic flywheel model, dubbed internally (with an ample dab of corporate mythos) as The Virtuous Cycle, in their e-commerce business before expanding its mechanics to fulfillment and cloud services.

The Virtuous Cycle, as drawn by Amazon.

This post is the first of two looking at the Amazon flywheel, how Amazon expanded it to their core and third-party businesses, and how we might see this strategy applied to global distribution and fulfillment in the coming years. My guess is that we’ll continue to see Amazon expand their supply chain upstream to global suppliers (this will involve maritime trade) and downstream to end consumers (through sortation centers, air fleets, and urban same-day delivery services.) Amazon’s success in this supply chain expansion will come through the economic model of their flywheel and their ability to power said flywheel through third-party service revenue.

Today, I’ll focus on the flywheel itself.

Here’s Brad Stone from his book The Everything Store on the “discovery” of the Amazon flywheel during a company offsite in 2001:

“Bezos and his lieutenants sketched their own virtuous cycle, which they believe powered their business. It went something like this: Lower prices led to more customer visits. More customers increased the volume of sales and attracted more commission-paying third party sellers to the site. That allowed Amazon to get more out of fixed costs like the fulfillment centers and the servers they needed to run the website. This greater efficiency then enabled it to lower prices further. Feed any part of this flywheel… and it should accelerate the loop. Amazon executives were elated… after five years, they finally understood their business.”

There a number of businesses under the Amazon umbrella where the flywheel comes into play.

The first, as I mentioned earlier, is Amazon’s core e-commerce retail business. Through the explosive growth of the Internet, Amazon worked directly with book distributors to give customers around the world the largest selection of books on earth. Since Amazon was the only bookstore that could offer this selection (no physical locations means the only limit on products offered is how consumers find them through keyword and taxonomy search,) they offered a unique customer experience, which in turn drove more traffic, which garnered the attention of more sellers, which increased Amazon’s selection, which improved the customer experience and so on.

But all of this was only part of the Amazon recipe for customer experience. The other half was lower prices, which, for a long time, Amazon mostly maintained through ruthless willpower. (An example: the “no-more-free-Ibuprofen” story.)

At a certain point in the late 90s, once the company had expanded their e-commerce offering to include music (CDs -- not streaming) and movies (DVDs -- wow,) Bezos and Amazon turned their focus on improving their inventory, warehousing, and distribution. This led to the first expansion of the flywheel.

The result was Fulfillment by Amazon, an Amazon-managed supply chain wherein Amazon stores inventory (their own and that of third-party sellers) in their fulfillment warehouses for distribution to shipping companies. For a long time, Amazon wasn’t perfect at shipping products. There were no robots. It was all done by hand, often times with Bezos or others in the company driving the truck to FedEx at the end of each day. It wasn’t until the initial growth of their e-commerce model that they were able to fuel an expansion in infrastructure that led to the automated Fulfillment Centers that we know of today.

It’s this reinvestment of profits back into the company’s infrastructure that Amazon’s probably best known for with analysts. Here’s their net income since launch (the visual comes from Ben Evans’s excellent post on why Amazon zeroes out its profits -- it’s a great read if you want to dive deeper into the subject):

Amazon has had a lot of revenue growth since they started in ‘95. There are two options when companies experience this type of growth:

-

Report profits to the street. See share price go up. Please shareholders. Maybe even hand out a dividend.

-

Reinvest back into the business -- track against Amazon’s net income from ‘95 to ‘13 to see how you compare. Listen to pundits lament your low-margin business. Watch share price do unfortunate things.

As seen by their net income (and their stock price plunge in the early 00s -- though there were other factors at play here to be sure,) Amazon chose the latter. I’ll take this moment to factor Amazon’s decision to invest in both infrastructure and improved efficiency into a revised copy of the flywheel -- below. (Efficiency and cost structure are synonymous in some circles, but I think it valuable to break it out for purposes I’ll outline in next week’s post.) Amazon didn’t just achieve lower cost structures through economies of scale, they did it by focused investment and a relentless bent on improving efficiency. This last piece will come into play later during the deep dive on Amazon’s supply chain.

With this reinvestment of growth back into their infrastructure, Amazon saw returns on efficiency and cost, which fed the flywheel through the enablement of lower prices for customers.

What’s interesting about FBA, is that it enabled a second driver of growth that operated in parallel with the core e-commerce business. That driver of growth was third-party fulfillment by Amazon. Once Amazon scaled out its FBA operations, it could offer them as a service to third parties at a lower cost (or percentage of mindshare) than what those B2B customers managed previously. As more and more of these third-party customers signed on for FBA, moving their product inventory, packing, and routing all into the Amazon FCs, Amazon fueled even more growth, which they could invest back into infrastructure, further lowering costs, making them even more competitive and so on. Here’s another great chart from Evan’s post that illustrates how big FBA services have become for Amazon:

The other (and probably best publicized) example of flywheel expansion is AWS. Initially started as a project to help with internal distribution of computing resources, AWS, fed by the Amazon growth engines of the core e-commerce business and FBA, scaled until it could offer its services to third parties. At that point, AWS customers became yet another engine of growth for the Amazon flywheel, and the cycle continued.

There’s a recurring theme here. By maintaining an unrelenting focus on the customer experience (great selection, low prices, fast delivery) and reinvesting profits back into infrastructure, Amazon reduces cost structures and often finds new businesses that serve as growth engines for the Amazon flywheel.

In next week’s post, I’ll focus on Fulfillment By Amazon, where the Amazon supply chain starts and stops today, and how that might change in the future. There’s more efficiency for Amazon to unlock in the global supply chain and that efficiency will drive growth, which will drive cost structure savings, which will lower prices, which will…

Ah. The flywheel.

Article from Sam Seely